Amanda Snodgrass is going to miss the fruit trees. “It’s like I had 2,000 children and I don’t have them anymore,” she said.

Until two weeks ago, it was her job to keep the trees on a good path amid the sunlight and shadows of their red cliff enclosure. She was the horticulturist of the historic orchards in Capitol Reef National Park in Utah, where fruit trees have been grown for nearly 150 years.

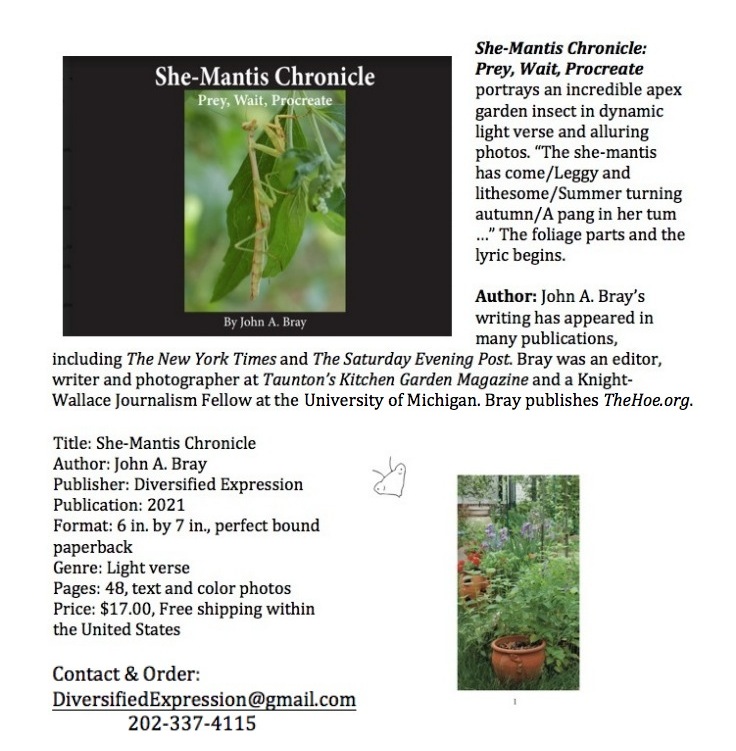

FRUITA: Orchards at Capitol Reef National Park in Utah brush up against raw geology. Photo Credit: Olivia Bray

Some of the original trees remain in Fruita, as the orchard community is called. But keeping up the 80 acres of orchards, where tourists and local residents throng to pick a cornucopia of fruit, takes a strong and sensitive hand on the harsh terrain.

“It’s difficult to have proper watering regimes, difficult to replace trees,” said Snodgrass. “Soil conditions need to be addressed.”

Trained in sustainable agriculture at Iowa State University, Snodgrass came to the Park in 2012 as an intern, took a position as orchard manager and then became horticulturist. She worked on rejuvenating the orchards, while preserving historic conditions and practices.

In the high desert, water is precious and becoming more so. The mountain snowpack has thinned; rain has dwindled; it’s gotten a little warmer, Snodgrass said.

Snodgrass

Irrigation, which draws on the Fremont River, is tightly regulated by state and local authorities. Five valves at the Park flow water into a gravity-powered system of ditches and bouts, and then into tightly spaced, shallow furrows that traverse the orchards.

Using a network of gates, water gets rotated around the orchards. Individual trees may only be irrigated once a month. Some roots, at least those of mature trees, can reach groundwater 6 to 8 feet below the surface.

“We have a meter that is checked every day that reads our flow rates. Everyone downstream still has to receive a portion of their water,” she said. “Each year, the water allotments get cut more and more, earlier and earlier in the season.”

Keeping Park Orchard Preserves

Planted by Mormon pioneers and under National Park Service control since 1971, the Capitol Reef orchards are among the largest historic fruit tree collections in the National Park Service. But scores of NPS sites include orchards. Upkeep varies, according to Jim Roche, acting chief of resource management and science at Capitol Reef, where a successor horticulturist is being sought. For example, at Yosemite, a previous posting for Roche, the orchards are merely protected, not actively managed. “It’s a wildlife issue. They draw in the bears,” Roche said. “We organize to pick the apples very quickly, mainly to reduce human-bear interaction.”

At bearless Capitol Reef, tree holdings, inventoried by a Northern Arizona University team, have fluctuated. The tree array includes apple, cherry, peach, quince, walnut, pecan and almond.

“Some of the original Golden Delicious were my absolute favorites. It was only certain trees,” Snodgrass said. “When initially planted, there was still some genetic variability, even in a single variety.” Oddballs exist, too. “The Winter Banana is fun because it actually tastes a little bit like bananas, but it doesn’t have a great texture.”

GOLD RUSH: Weighing in my harvest in mid-August of Ginger Gold apples at $1 per pound at the gate of an orchard at Capitol Reef National Park. Photo Credit: John A. Bray

Genetic testing indicates that three varieties of original trees do not exist anywhere else in the world. At times, more modern varieties have been planted, but the emphasis has been on preservation.

The historic figure of about 2,800 trees rose to a peak of about 3,200 under Park management, but the count has fallen to about 2,400 now, with pressure from disease and old age. And soil replant disease, a common complex of various ground organisms that undermine tree health, doesn’t help. Mature trees are better positioned to resist because they have grown in tandem with the damaging soil bacteria and nematodes. New plantings are more vulnerable.

“Typically, in a production orchard, in between plantings, you have to sterilize the soil because the disease pressure is too high,” Snodgrass said. “That’s for intensive commercial production.”

Commercial operations, which Snodgrass described as a “whole different ballgame,” don’t fit with demands for preserving historic methods and conditions in the Park. Still, much can be done to blend past and present practices. “Creativity is the key,” Snodgrass said.

To combat codling moth, an apple menace around the world, tree trunks were wrapped with corrugated cardboard bands, grooves against the bark, to entice descending larvae looking for comfortable places to overwinter. The plan was to trap the bugs and remove them with the cardboard. Holes started appearing in the bands.

“Woodpeckers decided it was a lunch buffet,” said Snodgrass, whose studies included integrated pest management. “It was a labor-intensive practice, but we didn’t have to destroy anything. The local birds took care of it.”

“Honestly, a lot of those trees are very tough,” she said, noting they also must grow in ground short on main nutrients, such as nitrogen. “I would call it a wild system to a certain degree.”

Meanwhile, most of the produce gets picked by Fruita-philes among the roughly 1.4 million people per year who now visit the Park, with lines forming at times, especially for peaches, according to Snodgrass. She is now a botanist at Klamath National Forest, located in northern California and southern Oregon.

“I worry about them,” Snodgrass said of her former charges. “But I know they’ll be OK.”

(See, National Park Beauty Shooting)

________________